Learning about learning

Then we began the excuses and dismissals for people who had relatives involved in a trial, the jobs that would create hardship, the grandmother traveling overseas for the birth of a child who would miss several months, etc, and one by one, the pool diminished and a replacement was added. We were close to being finished, and a "what about...." question arose from a final candidate. She was dismissed, and my name was drawn. <Cue Perry Mason music> What the heck, I figured. You can always learn something, right? I have fond childhood memories of the Perry Mason theme song playing as I walked down the hall to bed every night. It was one of my grandfather's favorite shows and it came on after the 11:00 news. Sworn to SecrecyOur training included very stern instructions that we were not to discuss the proceedings of the trial with anyone. Spouse. Mother. Therapist. Nada. No one. It was especially important because this is Rhode Island, and as a small state, six degrees of separation is more like 2.31, so we aren't allowed to talk about the cases. I can tell you that it's like watching a mashup of Law and Order where the case changes at each commercial break. We've had 16 cases so far, and I've filled up three notebooks, which, by the way, must be left in the courtroom, along with the officially appointed court pen. We may not bring our cell phones past the security guards (lest we record something!) though we can house them in a little phone locker with the security staff by the metal detectors and sign them out at lunch. I was jonesing over that the first couple of weeks (How do I tell time?) but I got over that and now don't even bother to bring my iPhone along to sit in the little locker. So What Does This Have to Do with Learning?You may be wondering, since I can't talk about any of this, what it has to do with learning. LOTS! Let me explain. If you've gotten an email from me, you know my email signature quotes Ray Leblond and says, "You learn something every day if you pay attention." My reply signature asks, "What have you learned today?" and when I'm in business mode, I answer my phone, "It's a great day for learning!" so I'm pretty invested in this learning thing. One of the things that has been screamingly obvious to me about court proceedings is that lawyers ask questions to present facts. Not tell stories. It drives me nuts trying to keep a bajillion names, dates and places straight, often with terminology that's brand new to me. Generally, after a couple of hours, the groundwork that has been painstakingly laid down scattered brick by scattered brick comes together, but sheesh, it's an effort. I sit there wishing I had a chart or flow chart or some job aid to help me keep track of things. If they'd just let the witness tell a story! Nope. It doesn't work that way. Lawyers have specific directions they want the process to move in. Our ah-ha moments must be extracted from the facts, not their insights, I guess. Perhaps one of you lawyerly people might explain why and enlighten me. This seems much harder it needs to be. Statistics is Like That Too!

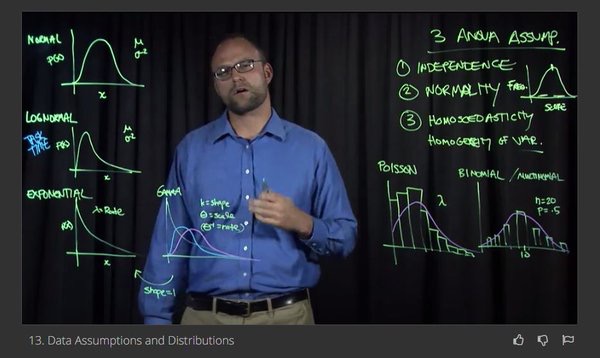

He presents a lecture like the one in the picture with all kinds of formulas and graphs and charts, then jumps into R Studio to show us how to enter the formulas to read the data in the exercise files. Type, click, control+enter and POOF! A bunch of numbers. That mean something. I have no idea what, but to the statistician, are really important. When he's done, we're sent off to take a multiple choice quiz on what he talked about, then complete a series of exercises to repeat what he did on the screen to try it out on our own. Lucky for me, Coursera embraces competency, and in most courses, allows you to take quizzes multiple times, giving you feedback to help you understand why your selection wasn't correct. (Mine usually aren't since I don't understand 80% of the content in this course.) The best thing this prof has done is to provide the formulas to correctly calculate things in R in the feedback. (God bless you, Dr. Wobbrock!!) We just have to substitute out the name of the file. This, I can do. I'm not sure why, but it does give me the right answer. So we're taking things like this: m = aov(Time ~ Tool, data=ide2) shapiro.test(residuals(m)) qqnorm(residuals(m)); qqline(residuals(m)) shapiro.test(ide2[ide2$IDE == "Illustrator",]$Time) shapiro.test(ide2[ide2$IDE == "InDesign",]$Time) and getting number strings as answers. Can I make the formulas compute the numbers? Yup! Do I understand what I'm doing? Nope. Could I take a data set and figure out how to do something with it, selecting the right test and plotting the correct syntax to get it? Not on your life. I shall pass this course, but only because of the help given in the feedback of the wrong answers. Do I know statistics? Nope. Not really much of an inkling. My big picture definition says that statistics is a method of validating that something is different from something else using a plethora of named tests that identify something unique for each one. There are t-tests and p scores and variables. I'm not sure I'm ready to put it into the bin with calculating ROI formulas yet, but it's pretty close. Maybe one of my geeky friends reading this can enlighten me on the value of all this. But it has given me some interesting insights on learning, and what we should and should not do in our learning. What's The "So What" of All This?

1 Comment

|

Jean Marrapodi

Teacher by training, learner by design. Archives

January 2018

Categories

All

|

Conference

|

Company

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed